Texas Republicans, at the urging of President Donald Trump, have redrawn their state’s congressional districts to give the GOP an advantage in next year’s midterm elections. The effort has led to a countermove by California to redraw its districts to give Democrats an edge. Several other states reportedly are considering similar moves.

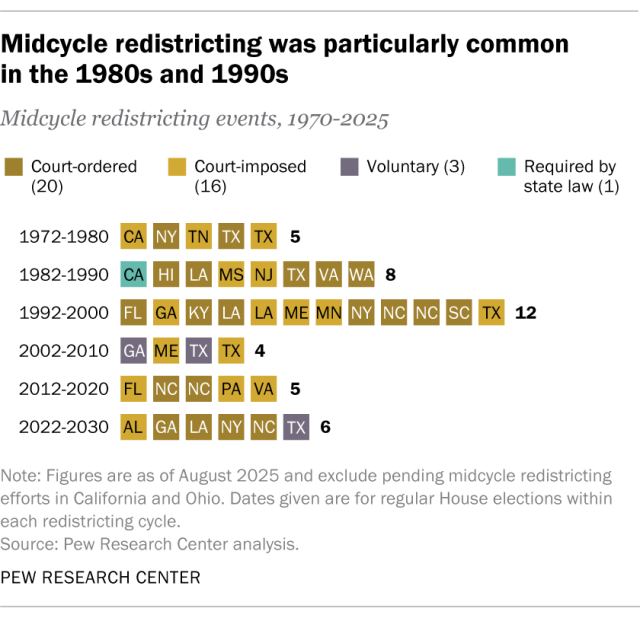

Midcycle redistricting efforts like the ones in Texas and California have, up to now, been extremely uncommon. Since 1970, only two states – Texas in 2003 and this year, and Georgia in 2005 – have voluntarily redrawn their congressional maps between censuses for partisan advantage, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis.

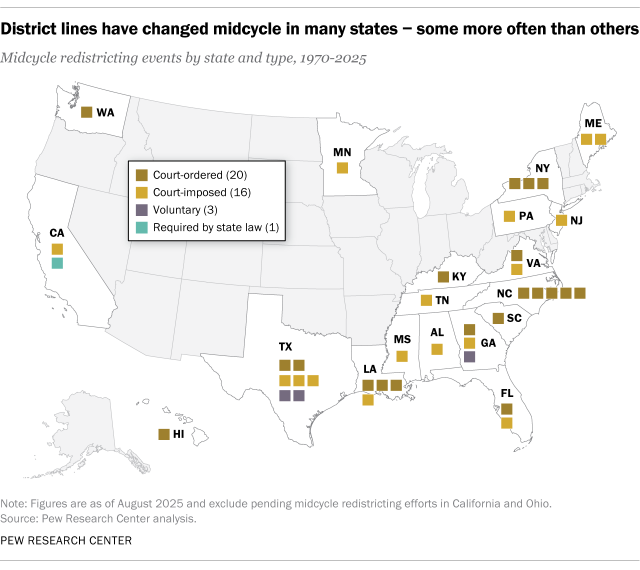

When midcycle redistricting occurs, it’s usually because courts have thrown out the previous maps for violating state or federal law. In fact, 36 of the 40 midcycle redistricting changes since 1970 have either been made in response to a court order (20) or imposed by a court itself (16). In addition to Texas and Georgia, California is also an exception: After the 1982 elections, lawmakers passed a revised version of the congressional map that voters had rejected in a referendum earlier that year.

After each decennial census, states must redraw their congressional districts to account for population shifts. A long series of court rulings, as well as state and federal laws, limits how those lines can be drawn.

In most states, most of the time, redistricting is a one-and-done proposition until after the next census. But in a handful of states, redistricting has long been a more contentious affair, with maps being repeatedly drawn, redrawn and re-redrawn.

Texas now and in 2003

Currently, Texas sends 25 Republicans and 12 Democrats to the U.S. House. (One of the state’s 38 seats is vacant because Rep. Sylvester Turner, a Democrat, died earlier this year.)

Texas Republicans hope their proposed new map will result in Texans electing five more Republicans – and five fewer Democrats – to Congress in 2026. Democratic state lawmakers didn’t have the votes to defeat the new map but temporarily blocked it by leaving the state, depriving the Texas House of a quorum to do business.

This summer’s events in Texas may, for those with long memories, evoke a very similar set of circumstances in 2003.

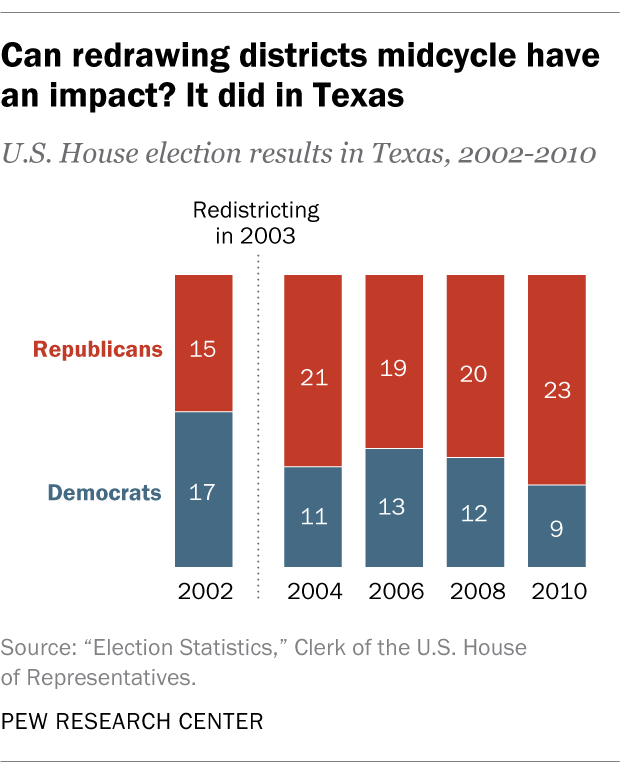

The saga began after the 2000 census, when the state’s Democratic-controlled House and Republican-controlled Senate couldn’t agree on a new congressional map. A federal court drew one that was later used in the 2002 midterm elections. That November, Democrats won 17 of Texas’ 32 U.S. House seats, versus 15 for Republicans.

Simultaneously, Texas Republicans also won a majority in the state House – meaning the GOP had full control of the state’s legislative and executive branches. Upon taking power, Republicans proposed to redraw the congressional boundaries, even though the court-drawn map would have remained valid through the 2010 election.

That move triggered multiple special sessions, walkouts by Democrats and other maneuvering, but eventually the GOP-dominated legislature passed the maps it wanted. And in the 2004 election, Republicans picked up six U.S. House seats in Texas, bolstering their overall majority in Congress. Despite a subsequent court declaring that one of the new districts was illegal, most of the GOP gains held for the rest of the decade.

Georgia in 2005

Two years after Texas passed its new maps, Georgia Republicans also were able to redraw congressional district lines in their favor after winning full control of the state legislature.

The process in Georgia was much less contentious than in Texas, perhaps because Republicans emphasized making districts more compact rather than maximizing their potential gains. But Georgia Republicans also hoped to bolster a vulnerable incumbent and bring two Democratic-held seats within reach. In the end, though, the partisan makeup of the state’s congressional delegation didn’t change under the new maps.

Midterm shifts in other states

In other states, legislatures have turned midcycle redistricting ordered by courts to partisan advantage. Consider, for example, North Carolina: The Tar Heel State is no stranger to redistricting controversies and is currently on its ninth congressional map since the 1990 census.

In 2016, North Carolina’s GOP-run state legislature was tasked with drawing a new congressional map after a federal judge struck down the old one as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. At the time, there were 10 Republicans and three Democrats in the state’s U.S. House delegation, and Republicans were determined to protect that dominance.

As one lawmaker famously said, “I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats, because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.” And that, in fact, is what they did. The new map was used in the 2016 and 2018 elections before a state court threw it out before the 2020 elections.

New York also has a long track record of recent redistricting controversies. In 2022, the state’s independent redistricting commission failed to agree on new maps, so the Democratic-led state legislature did so instead. New York’s highest court threw out that plan, and a lower court imposed its own. That year, Democrats won 15 of New York’s 26 U.S. House seats, and Republicans won the other 11.

But in December 2023, New York’s high court ruled that the court-drawn maps couldn’t stay in place indefinitely and the commission and legislature had to try again. In February 2024, the legislature rejected the commission’s plan and enacted its own instead. That year, Democrats won 19 seats and Republicans just seven.

These sorts of moves recall an earlier time in U.S. political history, when redistricting was openly wielded for political gain. Ohio, for example, was notorious in the 19th century for frequently redrawing district lines to advantage one party or the other.

Between 1876 and 1892, as Republicans and Democrats traded control of Ohio’s legislature, lawmakers redrew the state’s district lines seven times. Five straight U.S. House elections (1878 to 1886) were conducted under different maps.

In fact, Ohio is up for its own round of midcycle redistricting soon. The map adopted in 2022 by the state’s Republican-dominated redistricting commission didn’t have bipartisan support. Under Ohio’s constitution, that meant the map could only be used for two election cycles. So the legislature – or, if that fails, the commission – must take another crack at coming up with a plan for the 2026 midterms.

Utah may be joining the redistricting fray. A judge in that state has ordered the GOP-run legislature to redraw the map it adopted in 2021, after undoing much of a voter-approved initiative that sought to ban partisan gerrymandering and create an independent redistricting commission. Under the legislature’s map, Republicans won all four of Utah’s U.S. House seats in both 2022 and 2024. Legislative leaders reportedly are considering an appeal.

CORRECTION (Nov. 13, 2025): The chart “Midcycle redistricting was particularly common in the 1980s and 1990s” has been corrected to move Virginia’s court-ordered redistricting event to 1992-2000 and adjust the totals for 1982-1990 and 1992-2020 (seven and 13, respectively).