Religious identity is fading in many countries. From 2010 to 2020, the share of the population that was affiliated with any religion dropped at least 5 percentage points in 35 countries, according to a recent Pew Research Center study. It dropped considerably more in countries such as Australia (17 points), Chile (17), Uruguay (16) and the United States (13).

A new academic paper by a group of international scholars proposes that drops in religious affiliation happen in the medium and late stages of a “secular transition” process. This transition unfolds slowly, as generations are replaced by less religious ones.

Using data from the Center’s surveys in 111 countries and territories, the paper says that this process is affecting countries on every populated continent, including countries in which Christianity, Islam, Buddhism or Hinduism is the largest religion.

The paper was published in Nature Communications, a peer-reviewed academic journal. It was written by Jörg Stolz and Jean-Philippe Antonietti of the University of Lausanne, Nan Dirk de Graaf of the University of Oxford, and Pew Research Center’s Conrad Hackett.

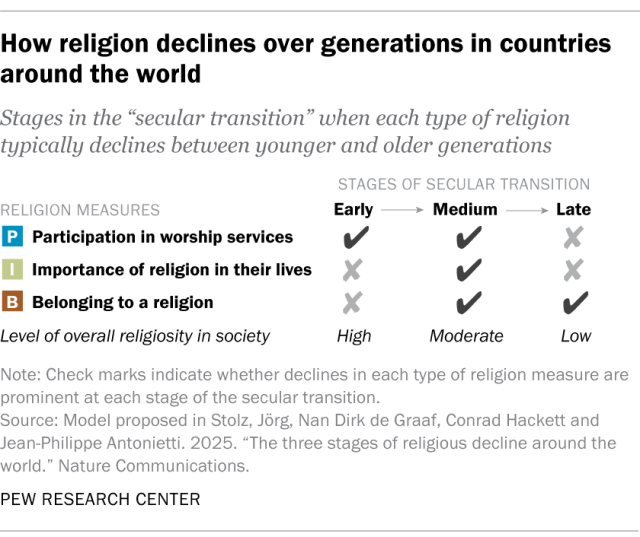

The authors write that religion generally declines between generations in three steps:

- People participate in worship services less often.

- The importance of religion declines in their personal lives.

- Belonging to religion becomes less common.

They call this the Participation-Importance-Belonging (P-I-B) sequence. In this sequence, generations first shed aspects of religion that require more time and resources. People are slower to shed religious identity, which is not necessarily as burdensome.

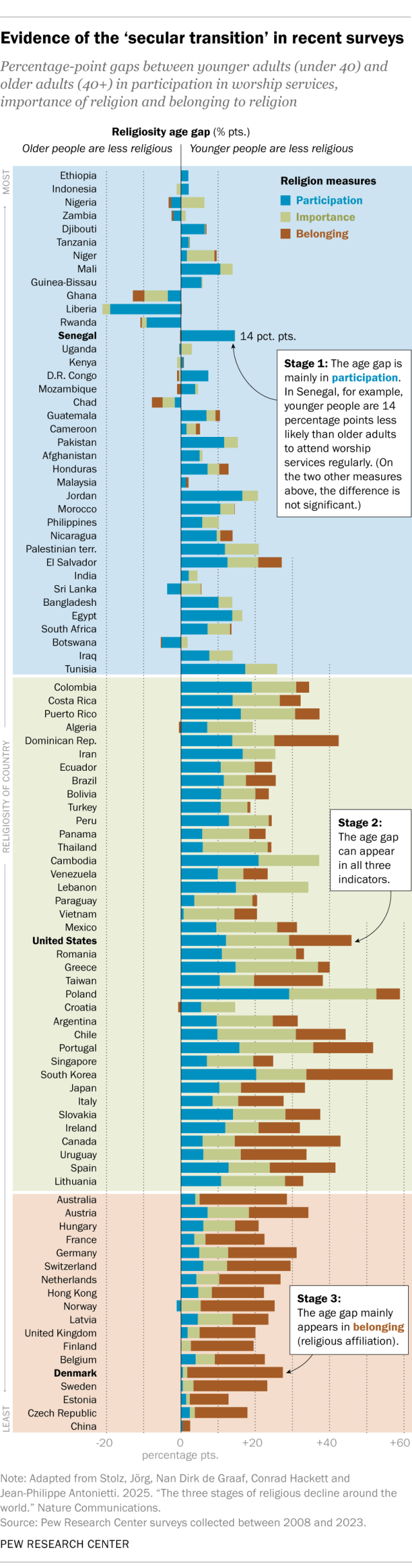

In the early stage of secular transition, generations differ primarily in their religious participation. In some countries that remain highly religious today, recent surveys show that each country’s share of adults under age 40 who frequently attend religious services has dropped below the share of older adults who do so.

Many African countries are currently in this early stage. For example, in Senegal, 78% of older adults attend worship services weekly, but younger adults are 14 percentage points less likely to do so. Yet almost all adults in Senegal – both young and old – still identify as Muslims and consider religion very important in their lives.

In the medium stage of secular transition, generations differ in their religious participation, importance and belonging. In countries that are moderately religious, all three steps in the P-I-B sequence are visible in recent surveys. Adults under 40 attend services less frequently than their elders, are less likely to say religion is important in their lives and are less likely to identify with any religion. This is the case currently in the U.S., along with many other countries in the Americas and Asia.

In the late stage of secular transition, generations differ primarily in religious belonging. The authors contend that this is because the first two steps have been completed. The shares of older adults who attend services and who consider religion important in their lives have already dropped to low levels, similar to those of younger adults. In the least religious countries today, the main difference between age groups is that younger adults are less likely to identify with any religion.

Many countries in Europe have reached this stage. For example, in Denmark, 79% of older adults remain religiously affiliated, but adults under 40 are 26 points less likely to say they belong to any religion. Attendance at religious services and self-assessments of the importance of religion are low among people of all ages.

Countries with different religious backgrounds tend to be at different stages of the secular transition. Among countries in the medium or late stage, the largest religion is typically Christianity or Buddhism. Muslim-majority countries and Hindu-majority India are in the early stage, and it’s not yet clear whether they will continue the process or stay as they are for a long time.

This secular transition isn’t completely uniform, and it may not be inevitable everywhere. Though the researchers argue that religion fades in this pattern in many places, a key difference between countries is when they start their secular transition.

In addition, there are some exceptions to the model. Eastern European post-communist countries with Orthodox or Muslim majorities, such as Russia, Azerbaijan, Moldova and Georgia, do not currently seem to follow the P-I-B pattern. These countries’ communist regimes suppressed religion, and since the collapse of the Soviet Union, they have had nationalist religious revivals.

Another exception is Israel, the world’s only Jewish-majority country. Israel has a large population of secular Jews, including many older people who migrated from the former Soviet Union. However, a large share of today’s younger Israelis were born to Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews. Overall, younger Israelis are similar to their elders on measures of religiosity.

The graphic below is adapted from Figure 1 in the “Three stages of religious decline around the world” article published in Nature Communications. It shows the Participation-Importance-Belonging sequence of differences in religiosity between younger and older adults in Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 94 countries and territories. Omitted are values from Israel and 16 Eastern European post-communist countries.